After smoothly wrapping up our first Ottawa performance, we took advantage of a day off in our schedule to visit Canada’s Parliament Hill. The scenery was exquisite—on the banks of the Ottawa River we stopped in front of three majestic gothic buildings surrounding a vast green quadrangle. What fascinated me most was not just the beautiful scenery, but the kind of ambience of freedom that makes one’s heart feel happy and light. Scanning the area around me, I couldn’t see one policeman in full armor, instead I saw all kinds of tourists—some taking photos, some cheerfully chatting and laughing, some strolling through the square, and some shuttling to and fro between the buildings.

Having grown up in China, I’ve become too accustomed to strict security being the order of the day in the capital. At the National People’s Congress adjacent to Tiananmen Square, you walk three steps and there’s a guard, walk five steps and there’s a sentry. Faced with such a “careless” Parliament Hill, I couldn’t help being a little wide-eyed and tongue-tied. What could cause the governments of two countries of the same era to have such a vast contrast? One man standing on the square gave me an answer.

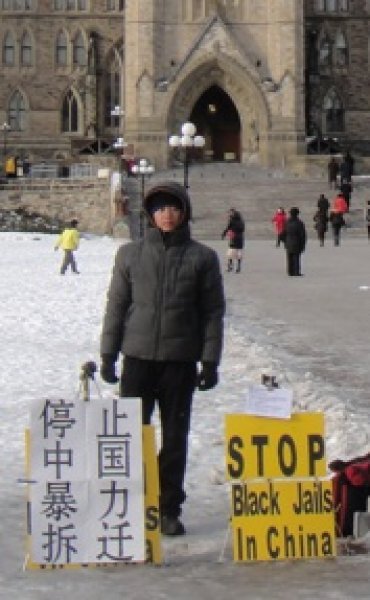

A man in his twenties, wrapped in a thick down coat, stood peacefully in one corner of the square. In front of him were two cardboard signs. One read in Chinese: “Stop Forced Evictions in China,” and another in English: “STOP Black Jails in China.” Through chatting with him, I came to know that his parents in China were forcefully evicted from their homes, and they were left with no choice but to petition the government for redress. When they did, they were sent to a “black jail,” an extralegal detention facility where detainees have no rights and are regularly abused. To rescue his loved ones, he goes there every day and stands for many hours. He does this not only for his relatives, but also for those countless of other innocent petitioners repeatedly imprisoned in China.

His face was red from the bitter cold, and his hands were tightly shoved into his coat pockets. From time to time he would shuffle his feet to keep the blood flowing, but in his eyes he had not a trace of resentment; on the contrary, he had a gentle composure and an air of determination.

He reminded me of a group of people, a group of people who for the sake of defending freedom of belief likewise are not deterred by wind or rain—Falun Gong practitioners. They are illegally jailed, savagely beaten, have their property confiscated, their families broken and scattered—just because they are not willing to give up their faith. Be it when the wind is piercing cold and the ground is frozen hard, or under the scorching sun, they unyieldingly go in front of Chinese embassies and sit in silent protest to defend their rights; they do so without complaint and with no regret. Every time I catch sight of their resolute figures, I’m moved by their persistent spirit, the kind of spirit Du Fu described in his Tang dynasty poem: “My one hut blown away, my freezing to death, none of that matter!”

At the same time, I also felt a sense of bitter satire. A country’s government not only cannot protect its own people, but uses ruthless means to persecute them and force them to flee to other countries and beg their governments for asylum. And then they are accused of being traitors, accused of colluding with foreign anti-China forces, and so on.

So it’s not hard to explain why in democratic countries the government is open to its citizens, but under the Chinese Communist Party’s leadership, the government is forever a restricted zone.

What made me even more bitterly disappointed was seeing how so many Chinese people just react with numbness. Or even more absurdly, they perceive any voice different from the Communist Party’s to be treason; even if people are hacked to pieces, they’re just reaping what they’ve sown. So when Chinese tourists on Parliament Hill saw the “Stop Forced Evictions in China” sign, the expression in their eyes betrayed disdain, even disgust, as if the sign was causing China an international loss of face. But it was precisely those blond-haired, blue-eyed Canadians who stopped by to inquire, encourage and support.

As Chinese people, we really should check our consciences—when we spend a joyful New Year with our loved ones, enjoying family warmth and happiness, how many people are enduring the pain of a broken and dispersed family? When our eyes our blinded by wealth and pursuit of a life of pleasure, how many children whose parents were persecuted to death now wander the streets, destitute orphans with no one to depend on? Does it really “serve them right” to suffer from the government’s outrageous abuses? A new year has begun, and one question worth pondering is: What course should China’s future follow?

Ophelia Wu

Principal dancer with Shen Yun's Touring Company

January 12, 2011